Image

You should really subscribe now!

Or login if you already have a subscription.

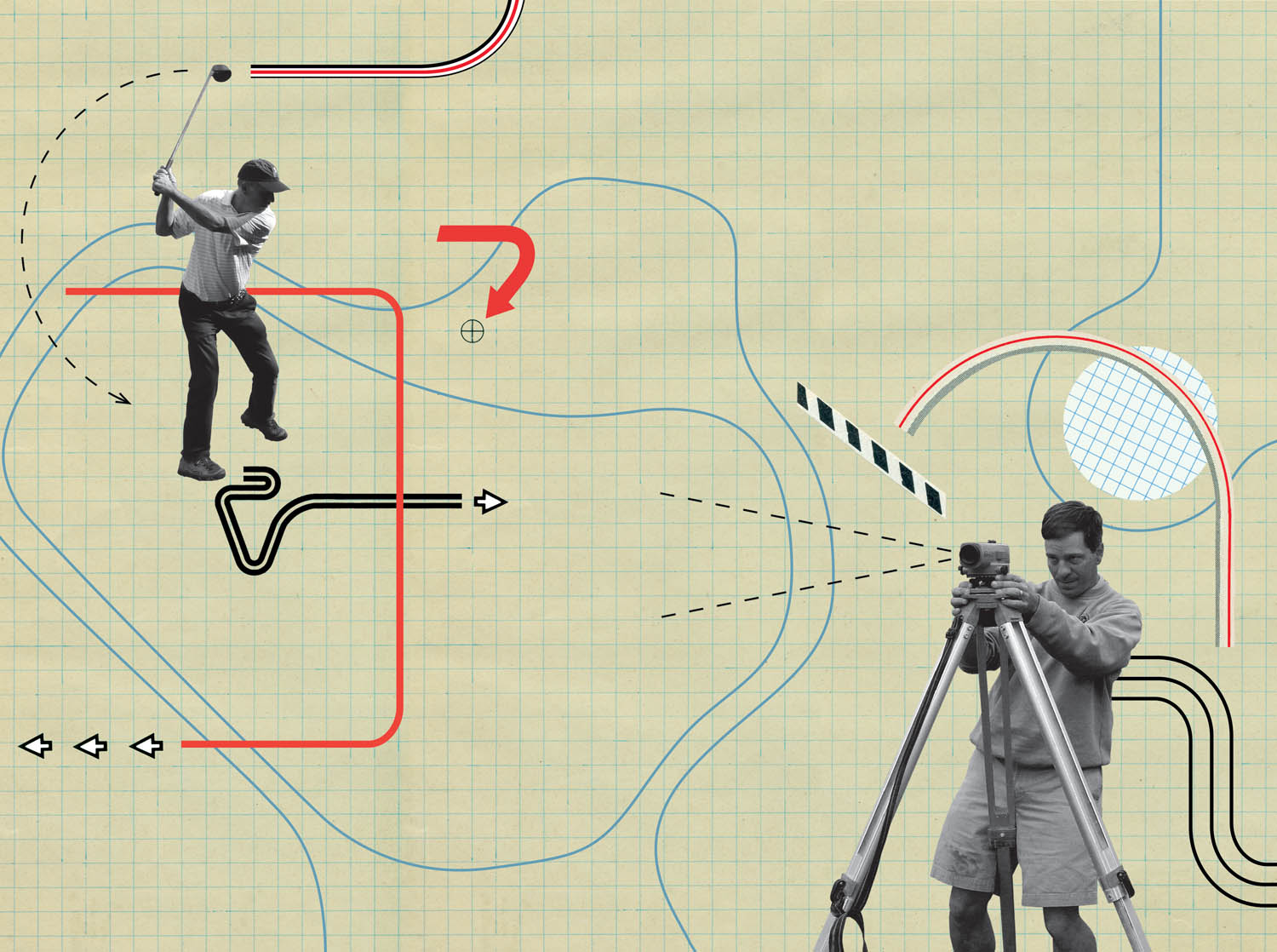

Bill Zindel is an artist, illustrator, and graphic designer. He is a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design and teaches printmaking at NIAD Art Center in Richmond, California.